Weaponizing the periodic table

China won this war without firing a shot

I’ve been sitting on this one for a while now. Collecting data points that most people missed because they were too busy arguing about tariffs and TikTok bans.

But the trade war is heating up again I think. Inevitably I have to add. And when it does - when the next round of restrictions hits and everyone acts surprised - I want this here.

Because what’s coming isn’t another tariff dispute that gets negotiated away. It’s strategic strangulation through materials nobody can pronounce or understand.

This one’s going to be heavy on the numbers. I’m talking percentages, production figures, price movements, stockpile comparisons, the whole data-laden works. Because when you’re discussing whether the United States can manufacture ammunition, fighter jets, or data centers without Beijing’s permission, vague hand-waving doesn’t cut it. The specifics matter. The percentages matter. The timelines matter.

So buckle up.

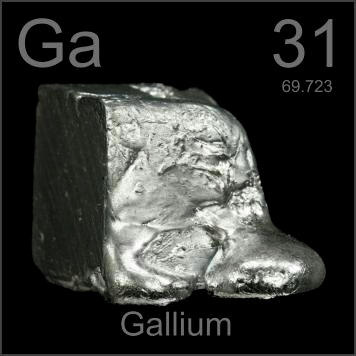

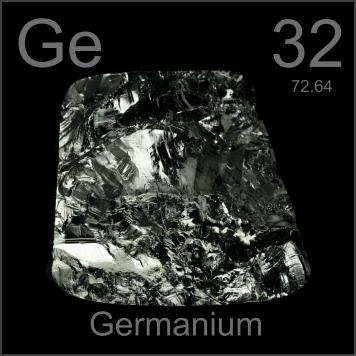

In July 2023, China announced export licensing requirements for gallium and germanium. The announcement received approximately the coverage you’d expect for a mid-tier commodity story - which is to say, almost none. Commodity traders noticed. Defense analysts should have noticed. The general public remained blissfully unaware that Beijing had just proven it could shut down semiconductor manufacturing worldwide whenever it chose to do so.

China controls 94% of global gallium production and 83% of germanium. But more importantly, China had demonstrated the template. Not an outright ban. Not a dramatic announcement with threats and posturing. Just licensing requirements. Applications welcome. Processing times... variable.

The licenses, in practice, never came.

By August 1, 2023, when the gallium controls took effect, Chinese exports had already collapsed. Not declined. Collapsed. European buyers scrambled for inventory that increasingly did not exist at any price. The message was unmistakable, delivered in bureaucratic language that Western governments somehow failed to translate into strategic alarm: we control what you can build, and we can turn it off whenever we want.

October 2023 brought graphite export controls. China produces over 90% of the world’s processed graphite, the material that enables lithium-ion battery anodes. Every electric vehicle. Every grid-scale battery. Every piece of consumer electronics. The West wants an energy transition? Beijing will decide the pace.

December 2023 escalated further. China banned export of rare earth extraction and processing technology. Not the minerals themselves - not yet - but the knowledge of how to extract and refine them. You can’t build an alternative supply chain if you can’t access the engineering expertise required to make it work. The technology ban meant that even if Western companies found rare earth deposits, they couldn’t efficiently process them without violating Chinese export controls.

Then came 2024.

September 15, 2024 marked the implementation of antimony licensing requirements. You probably didn’t hear about it. Antimony doesn’t have the cultural resonance of rare earths or the tech-sector visibility of gallium. The median American voter has never heard the word. The median congressional staffer cannot spell it. The median defense journalist could not identify its applications without research.

This obscurity was not incidental. It was the whole point.

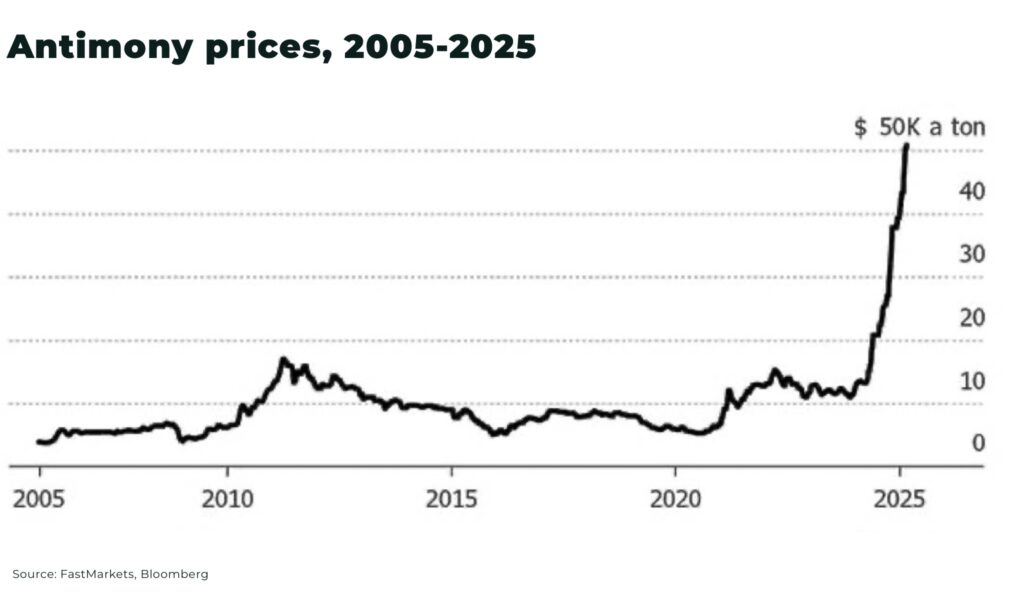

Because while nobody was paying attention, antimony prices exploded from around $11,300 per metric ton in January 2024 to $57,778 by April 2025. That’s 400% in eighteen months. Fastmarkets has tracked antimony since the 1980s and has never recorded a rally this steep. Ever. Not during the Cold War. Not during previous supply disruptions. Never.

October 1, 2024 brought comprehensive rare earth management regulations establishing traceability requirements and quantitative export controls. Then December 3, 2024 - one day after the United States added 140 Chinese entities to the Entity List - Beijing announced outright export bans on gallium, germanium, antimony, and superhard materials to the United States specifically. The first country-specific mineral embargo in the modern era.

Not licensing requirements. Not processing delays. An explicit ban targeting America by name.

April 2025 introduced export licensing for seven heavy rare earth elements: samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium. Notice what’s in that list? Dysprosium and terbium. The heavy rare earths that enable high-temperature permanent magnets in missiles, fighter jets, and precision munitions. Elements where China controls 99-100% of global supply with no commercial production anywhere else on Earth.

October 2025 brought five additional rare earths under control and introduced China’s version of the Foreign Direct Product Rule. Any product containing 0.1% or more Chinese-origin rare earth materials now requires Ministry of Commerce export approval. Beijing had effectively created extraterritorial control over global supply chains. A Japanese company making electric motors with Chinese neodymium? That motor cannot be exported without Chinese permission. An American defense contractor assembling missile guidance systems with Chinese dysprosium magnets? That system is subject to Chinese export approval.

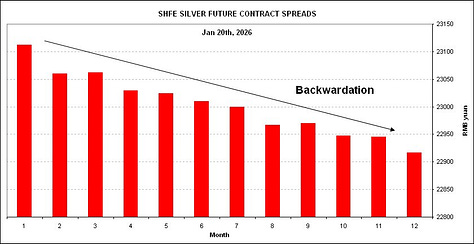

October 30, 2025 established new silver export rules requiring producers demonstrate 80+ tonnes annual output to qualify as exporters. Effective January 1, 2026. Existing exporters with proven 2022-2024 export history get licenses. New exporters face bureaucratic obstacles designed to exclude them. China consumes over 50% of global industrial silver for solar panels, electronics, and EVs.

Then came November 2025 and the supposed “suspension”. Following the Trump-Xi summit in Busan, China announced it would temporarily lift the December 2024 US-specific bans and pause the October 2025 extraterritorial controls. Western media framed this as de-escalation. A gesture of goodwill. Evidence that tough negotiating works.

Everyone missed three critical details.

The suspension expires November 2026. Right before US midterm elections. “Coincidence”?

The April 2025 heavy rare earth licensing remains in full force. Remember, those are the materials most essential for military applications… Still under strict controlled.

Exports to US military end-users remain permanently prohibited. The “suspension” only covers commercial applications. The Pentagon still cannot buy Chinese antimony. American defense contractors still cannot source Chinese rare earths for weapons systems. The temporary easing is a pressure valve, not a policy reversal. Maybe they can take the magnets out of washing machines like Russia does right?

All in all, Beijing demonstrated that it can cripple American defense production through mechanisms that the American public doesn’t see, cannot or will not understand. Through materials the American media cannot explain or pronounce, and through supply chains the American defense establishment failed to monitor. The demonstration was so effective that it produced minimal political cost while forcing the Pentagon into emergency procurements that will take years to execute.

This is what a victory looks like in 21st-century financial world war. No carriers that are sunk. No cities bombed. Just quiet, patient exploitation of dependencies that nobody noticed until the moment they mattered most.

Two weeks ago, on January 6, 2026, China banned exports of dual-use items to Japan. Effective immediately. No grace period.

Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi had said in November that a Chinese naval blockade of Taiwan could constitute “a situation threatening Japan’s survival”. Beijing waited exactly eight weeks, then delivered the response: you cannot have rare earths for military purposes. You cannot strengthen your military capabilities using Chinese materials. Export licenses for defense contractors? Denied.

Japan imports 60-63% of its rare earths from China. The ban covers the entire dual-use catalog - over 1,000 items including samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium. The heavy rare earths essential for high-temperature magnets. The elements that enable F-35 actuators and missile guidance systems and advanced electronics that operate in thermal environments where standard materials fail.

November 2025 Chinese customs data showed rare earth exports to Japan surging 35% year-over-year. Japanese companies saw this coming. They stockpiled.

Tokyo called the move “unacceptable and deeply regrettable”. Beijing’s Commerce Ministry spokesperson explained that exports would only affect military firms, not civilian users. This distinction is meaningless. In modern supply chains, civilian and military applications use identical materials. The separation exists on paper, not in physical reality. A magnet manufacturer cannot segregate rare earth oxides by end-use during chemical separation. The restriction functionally applies to any entity that might possibly supply defense contractors, which is most of the industrial base.

But the pattern should be clear by now. A fishing boat incident in 2010? Rare earth cutoff to Japan. Taiwan comments in 2026? Rare earth cutoff to Japan. The weapon gets tested periodically to ensure it still works. Each test teaches Japan how dependent it remains despite fifteen years of diversification efforts. Despite Australian supply agreements. Despite recycling initiatives. Despite strategic stockpiles. China still controls the chokepoint and everyone knows it.

September 23, 2025. The Defense Logistics Agency awarded United States Antimony Corporation a sole-source, five-year contract worth up to $245 million to supply approximately 6.7 million pounds of antimony metal ingots for the National Defense Stockpile. The phrase that should have alarmed everyone was “sole-source”. Not a competitive bidding process. No alternative suppliers evaluated and rejected on merit. A sole-source contract because United States Antimony Corporation operates the only antimony smelters in North America.

There are no others.

USAC runs two facilities: Thompson Falls, Montana (currently producing 160 tonnes per month, expanding to 500-600 tonnes) and Madero, Coahuila, Mexico (ramping to 200 tonnes per month, potentially scalable to 1,000 tonnes). That’s it. That’s the entire North American antimony smelting industry. Two facilities owned by one company headquartered in Thompson Falls, Montana, population 1,319.

For context, USAC’s entire 2024 revenue was $14.9 million. The September contract represented sixteen times their annual revenue. But that wasn’t the end. USAC announced total secured contracts exceeding $352 million by November 2025. Revenue guidance for 2026: $125 million, excluding additional antimony trioxide contracts under negotiation.

The company describes itself as “the only fully integrated antimony operation outside of China”. That self-description is not marketing hyperbole. It is a factual statement about the structural fragility of American ammunition production.

October 2, 2025. Montana Department of Environmental Quality approved USAC’s operating plan modification for Stibnite Hill. October 7, 2025. USAC began mechanized exploration and bulk sampling. By late 2025, more than 250 tons of stibnite ore had been hauled to flotation mills for assay and test work. USAC staked 102 federal claims and expects new furnaces at Thompson Falls to be operational in January 2026 - exactly as planned.

The stock market noticed. UAMY traded at $1.21 in January 2025. By mid-January 2026, it traded between $7.65 and $8.29 - up 516% over 52 weeks. Market capitalization expanded from under $200 million to approximately $1.07 billion. Four analysts rate it “Strong Buy” with price targets around $9.67.

Antimony’s function is simple: antimony trisulfide ignites when a firing pin strikes a primer. Without it, bullets do not fire. Artillery shells do not detonate. Over 300 types of American munitions - from 5.56mm rifle rounds to 155mm howitzer shells - require antimony in their primers. Colonel Steven Power of Picatinny Arsenal, the Army’s primary research and development center for armaments, used the phrase “essential and non-replaceable component” in congressional testimony that received virtually no media coverage.

He used “non-replaceable” because it’s true. There is no synthetic substitute. There is no alternative compound. There is no workaround that maintains military specifications. The physics and chemistry of percussion ignition require antimony. The requirement is not negotiable.

Now recall what China did. August 14, 2024: antimony export licensing announced. September 15, 2024: licensing takes effect, shipments collapse by 97%. December 3, 2024: explicit ban on exports to the United States. And now the price trajectory: $11,300 per ton (January 2024) to $22,700 (May 2024) to $38,000 (December 2024) to $57,778 (April 2025).

And the US stockpile? Approximately 1,100 tons. Down from 27,000 metric tons in the 1990s. Current holdings represent 4-5% of annual US consumption of 23,000-24,000 tons. At current usage rates, the National Defense Stockpile contains maybe forty-two days of antimony. Not months. Days.

Congress sold off strategic reserves systematically since 1992 because “global markets will always provide”. The entire National Defense Stockpile collapsed 98% in value from $9.6 billion in 1989 to $888 million in 2021. Current holdings meet only 37.9% of military needs and less than 10% of essential civilian needs in a national emergency. The Government Accountability Office has been warning about this for years. Nobody listened.

Companies in the antimony space include United States Antimony Corporation (UAMY, NYSE American), Perpetua Resources (PPTA, Nasdaq - received $80 million+ in DoD grants for their Stibnite Gold Project in Idaho which contains substantial antimony), and Military Metals Corp (MILI, Canadian Venture Exchange - exploring antimony deposits in Slovakia). I have not researched these companies in depth. This is not investment advice. These are just names for those who want starting points for their own due diligence.

Beijing didn’t need missiles to prove it could cripple American ammunition production. It just needed patience and the structural monopoly that American policymakers failed to prevent and now cannot quickly undo.

And then there’s cesium. You’ve probably never heard of it. Most people haven’t. It doesn’t have the cultural resonance of rare earths or the tech-sector visibility of gallium. The median voter couldn’t identify its applications. The median defense journalist would need Wikipedia.

Cesium enables GPS navigation. Atomic clocks. Oil and gas drilling. Telecommunications infrastructure. Aerospace systems. The element that keeps global positioning working and enables precision timekeeping for financial markets and communications networks worldwide.

China controls the only two active cesium facilities on Earth. Not most of them. Not a dominant share. All of them.

Sinomine Resource Group operates the Tanco mine in Manitoba, Canada and the Bikita mine in Zimbabwe. That’s it. That’s the entire global cesium production infrastructure. Two facilities owned by one Chinese company.

The Canadian mine - yes, located in Canada - ships most of its output to China for processing. Because raw cesium ore has limited utility without refining infrastructure. And the refining infrastructure is Chinese-controlled.

For years Japan regularly purchased cesium-bearing pollucite from the Zimbabwean mine. Then Sinomine took over operations in 2022. Japanese buyers suddenly encountered difficulties accessing the facility. Attempts by Japanese officials to engage Zimbabwe’s Ministry of Mines proved unsuccessful. Exports to Japan ceased entirely.

The market is tiny - estimates range from $350 million to $600 million globally. Not enough revenue to justify Western investment in alternative capacity. But just enough strategic importance to matter when it’s cut off.

There’s no public spot market for cesium. Pricing is opaque. Sinomine controls both supply and price discovery.

A cesium restriction would cascade through systems most people don’t know exist. Financial markets lose precise timekeeping? Transactions fail. GPS accuracy degrades? Navigation systems become unreliable. Oil drilling operations lose cesium formate drilling fluids? Production slows. The disruptions would be technical, obscure, and devastating.

Nobody would understand the cause. The explanation requires three levels of technical detail that loses 95 percent of audiences. The public wouldn’t comprehend why critical systems stopped working. Media couldn’t explain it. Politicians couldn’t address it.

Maximum damage. Minimum comprehension.

Tungsten is already under restriction. February 2025 export controls are in effect. China controls 82-83% of global production and 59% of reserves. Tungsten carbide enables armor-piercing ammunition and kinetic energy penetrators for tank munitions. High-temperature aerospace applications. Cutting tools for manufacturing.

Vietnam produces about 4% of global supply. Russia has reserves. Neither represents a reliable alternative for obvious geopolitical reasons. The US imports roughly 50% of tungsten consumption, with significant portions historically coming from China. The National Defense Stockpile holds some tungsten, but quantities aren’t publicly disclosed in detail - “we have it, trust me bro”!

Tungsten restrictions matter. But they’re also somewhat expected. Military applications are obvious. Alternative suppliers exist, however constrained. It fits the pattern people understand about critical minerals. Which makes it less effective as a strategic surprise.

Let’s move to something less obvious.

Bismuth flew completely under the radar until February 2025, when China imposed export controls that caused prices to surge seven-fold from $4 per pound to $40-55 per pound. I’ll bet you’ve never even thought about bismuth. Most people haven’t.

China controls 68-80% of global bismuth production and refining. The United States ceased primary bismuth production in 1997. There is no government stockpile. Zero. Because bismuth was always considered a byproduct of lead and copper refining, easily available from global markets, nothing to worry about.

Then in June 2025, the “Magnificent Seven” tech companies - we’re talking Apple, Microsoft, Google, the entire AI infrastructure buildout - warned that bismuth-based solder shortages could halt data center construction. AI chips require lead-free solder due to environmental regulations. Bismuth-tin alloys are the primary alternative. No bismuth? No solder. No solder? No AI data centers.

Military applications include radiation shielding, lead-free ammunition (because conventional lead ammunition faces environmental restrictions even for defense), and temperature-sensitive electronics soldering. Bismuth has a melting point of 271°C, which makes it ideal for applications requiring precise thermal management.

The price spike was brutal and nobody was prepared. February 2025: controls announced. Within months: seven-fold increase. The semiconductor industry and defense contractors suddenly competing for the same constrained non-Chinese supply. One policy framework must yield. Take a gander which one?

Companies mining or processing bismuth are scarce. 5E Advanced Materials (FEAM, Nasdaq) processes boron and has bismuth exposure through their critical minerals focus. Korea Zinc is a major refiner but not directly accessible to most US investors. This market is thin, which is precisely why the restriction is so effective.

What makes bismuth particularly insidious is that it demonstrates maximum leverage with minimum visibility. The general public cannot understand why data centers aren’t being built. The explanation requires three levels of technical detail that lose 95% of audiences. Perfect weapon.

Everyone knows the Democratic Republic of Congo produces most of the world’s cobalt. What they don’t know - what the simplified “cobalt comes from Africa” narrative obscures - is that China controls fifteen of the nineteen DRC cobalt mines. China Molybdenum Corporation (CMOC) alone controls 41% of the global cobalt market through its ownership of Tenke Fungurume.

The DRC produces 74-76% of mined cobalt. But China refines 73-77% of global supply. This distinction matters because cobalt ore from the DRC has limited utility without refining infrastructure. And the refining infrastructure is Chinese-controlled, either through direct ownership or through contracts that give Chinese entities first right of refusal on output.

Cobalt’s primary military application isn’t batteries. That’s the civilian narrative. For defense, cobalt enables jet engine superalloys. Over 50% of US cobalt consumption goes into superalloys, not batteries. Cobalt-chromium-tungsten alloys operate at temperatures exceeding 1,000°C while maintaining structural integrity. Every advanced jet engine - the F-35, F-22, commercial aircraft turbines - requires these alloys.

The F-35 specifically contains approximately 50 pounds of samarium-cobalt magnets. Not neodymium-iron-boron magnets like civilian applications. Samarium-cobalt magnets maintain magnetic properties at higher temperatures, essential for military electronics operating in extreme conditions.

China doesn’t need to cut off African cobalt mining. It just needs to control where refined cobalt goes. African mining creates the illusion of supply diversity while Chinese refining ensures control remains centralized.

US-listed companies with cobalt exposure include Glencore (GLEN, London, OTC: GLNCY), which operates the Mutanda and Katanga mines in the DRC. eCobalt Solutions went bankrupt. Jervois Global (JRVMF, OTC) suspended operations at its Idaho Cobalt Operations in 2023 due to low prices and inability to compete with Chinese-refined material. When you cannot compete with subsidized Chinese refining, Western production shuts down, increasing dependence.

Graphite represents battery warfare. China produces over 90% of the world’s processed graphite, specifically the spherical graphite required for lithium-ion battery anodes. You can mine graphite in various countries - Australia, Mozambique, Canada all have deposits. But processing raw graphite into battery-grade spherical graphite requires specialized facilities that exist almost exclusively in China.

The October 2023 export controls targeted this exact chokepoint. Not graphite in general. Specific graphite products essential for batteries. Natural graphite flakes, spherical graphite, high-purity graphite. The materials that enable energy storage.

Every electric vehicle contains 50-100kg of graphite in its battery. Grid-scale storage? Thousands of kilograms. Consumer electronics? Smaller quantities but billions of units. The West wants energy transition, wants electric vehicles, wants grid storage to enable renewable energy? Beijing controls the input materials. Again.

What makes graphite restrictions particularly effective is the timeline problem. Building spherical graphite processing facilities takes years and requires environmental permits that Western countries grant slowly. Canada’s Nouveau Monde Graphite (NMG, NYSE) has been working on battery-grade processing for nearly a decade. Australia’s Syrah Resources (SYR, ASX, OTC: SYAAF) operates the Balama mine in Mozambique but struggled with the Vidalia, Louisiana processing facility due to costs and competition from Chinese material.

The problem isn’t mining. The problem is processing economics. Chinese facilities benefit from decades of optimization, vertical integration, and state support that makes Western facilities uncompetitive even when they successfully start production. Which means even if you build alternative capacity, it may shut down during price dips, returning control to China.

China can throttle Western energy transition at will. The restriction doesn’t need to be permanent. Just long enough to make alternative investments economically unfeasible.

Gallium and germanium might seem like semiconductor industry concerns, technical materials that matter for chip manufacturing but lack broader strategic implications. That interpretation would be wrong.

China controls 94% of global gallium production and 83% of germanium. Both materials are critical for compound semiconductors - the gallium nitride and gallium arsenide chips that enable 5G infrastructure, satellite communications, radar systems, electronic warfare, and power electronics. These aren’t the chips in your laptop. These are the chips in F-35 avionics, Patriot missile systems, AEGIS radar, military satellite networks.

When China announced export licensing for gallium and germanium in July 2023, effective August 1, 2023, Western governments initially downplayed the impact. Stockpiles exist, alternative suppliers can ramp up, compound semiconductor applications are niche. Within three months, European and American buyers faced severe shortages. Prices spiked. Applications sat unfilled.

Gallium is primarily produced as a byproduct of aluminum smelting. Theoretically, any country with aluminum production could extract gallium. In practice, the extraction economics only work at Chinese scales and with Chinese cost structures. Recycling gallium from manufacturing scrap offers some relief but cannot replace primary supply.

Germanium comes primarily from zinc mining and coal ash. China’s dominance stems from its massive coal consumption - an ironic situation where environmental critics of Chinese coal power ignore that coal ash enables the semiconductor industry they depend on. Belgium’s Umicore recycles germanium. South Korea has some production. Neither comes close to Chinese output.

For military systems with 10-20 year development and procurement timelines, gallium and germanium restrictions creates an immediate crisis. You cannot redesign radar systems or satellite communications on short notice. The electronics are baked into platform architecture years before production starts. If China cuts off gallium when a major defense program is scaling up production, that program stops. No alternatives. No substitutions. Just delays measured in years while you redesign around component availability.

Companies attempting to build Western gallium production include AXT Inc (AXTI, Nasdaq), though they largely depend on Chinese raw material for their gallium arsenide substrate production. Umicore (UMI, Brussels, OTC: UMICF) handles germanium recycling. But nobody is seriously competing with Chinese primary production economics.

The semiconductor restrictions demonstrate something crucial: China can target specific technology sectors without broader economic disruption. Gallium and germanium shortages don’t affect consumer goods prices. They don’t trigger inflation that voters notice. They just quietly degrade Western military and telecommunications capabilities while the public remains completely unaware anything is wrong.

Now we get to the materials that represent existential threats. Not economic disruption. Not industrial inconvenience. Actual structural vulnerabilities that could halt Western military production and advanced manufacturing within weeks.

Starting with heavy rare earths.

China’s rare earth dominance is well-known by now. The 2010 fishing boat incident with Japan, the Deng Xiaoping quote about “the Middle East has oil, China has rare earths”, the general awareness that these elements matter for technology. What’s less understood is the distinction between light rare earths and heavy rare earths, and why that distinction determines whether American missiles can fly.

Light rare earths - lanthanum, cerium, neodymium - are not rare, they’re actually relative abundant. China dominates production but alternative sources exist in the US (Mountain Pass, California), Australia (Lynas), and elsewhere. Heavy rare earths - dysprosium, terbium, yttrium - are different. China controls 99-100% of global supply with no commercial production anywhere else on Earth.

Heavy rare earths enable high-temperature permanent magnets that operate above 200°C. Neodymium-iron-boron magnets work fine for consumer electronics and electric vehicles. But missile guidance systems? Fighter jet actuators? Precision munitions? Those operate in thermal environments that demagnetize standard NdFeB magnets. You need dysprosium-enhanced magnets that maintain magnetic properties at extreme temperatures.

The Government Accountability Office estimated that rebuilding heavy rare earth supply chains would require fifteen years. Not five years with aggressive investment. Not seven years with emergency measures. Fifteen years assuming everything goes right, permits are granted, deposits are found, processing facilities are built, skilled workers are trained, and production scales to military specifications.

It’s an absolute clusterfuck. 78% of Department of Defense weapons systems contain rare earth magnet components. Navy: 91.6%. Air Force: 85.1%. These aren’t optional enhancements. These are core components that cannot be substituted without complete system redesigns.

The April 2025 export licensing requirements specifically targeted dysprosium, terbium, and samarium. The three heavy rare earths most critical for military magnets. And remember, the November 2025 “suspension” explicitly exempts military end-uses. The Pentagon still cannot buy Chinese heavy rare earths for weapons systems. That restriction remains permanent.

Companies attempting to build Western heavy rare earth production face brutal economics. MP Materials (MP, NYSE) operates Mountain Pass but historically focused primarily on light rare earths. That changed dramatically in 2025.

July 10, 2025. The US Department of Defense announced a 10-year commitment to purchase MP Materials’ neodymium-praseodymium (NdPr) products at a guaranteed price floor of $110 per kilogram. The government simultaneously invested $400 million directly in MP Materials stock, making DoD the largest shareholder in the world’s second-largest rare earth mine.

The stock responded predictably. MP traded around $21 in January 2025. By mid-January 2026, it traded near $68 - up 225% year-to-date. Market capitalization expanded to approximately $12.2 billion. Analysts rate it “Moderate Buy” with price targets ranging from $71 to $79, though the consensus seems to be missing the strategic implications of having the US military as your largest shareholder with guaranteed offtake agreements.

MP stopped exporting rare earth concentrates to China in Q3 2025. Instead, the company now processes material domestically. The Fort Worth, Texas magnet manufacturing facility began commercial production in early 2026, targeting 1,000 tonnes per year - enough for approximately 500,000 electric vehicle motors. A second, larger facility announced in July 2025 will expand total capacity to 10,000 tonnes by 2028.

The $500 million partnership with Apple announced July 15, 2025 provides long-term guaranteed demand for American-made rare earth magnets produced from recycled materials. The government’s Defense Production Act Title III funding - $439 million across various rare earth projects - represents perhaps 3% of the estimated $14+ billion critical mineral shortfall. But for MP specifically, the combination of DoD investment, guaranteed price floors, and Apple offtake creates unprecedented revenue visibility for a mining company.

January 15, 2026 brought additional momentum: bipartisan legislation proposing a new federal agency with a $2.5 billion budget specifically to promote domestic critical mineral capabilities. The proposed Critical Minerals Independence Act signals that rare earth supply chain security has achieved genuine bipartisan support - a rare occurrence in contemporary American politics.

Lynas Rare Earths (LYC, ASX, OTC: LYSCF) remains the only significant non-Chinese rare earth processor and the only company outside China capable of separating both light and heavy rare earths at industrial scale. Recent quarterly results showed revenue up 43% as rare earth prices surged following China’s April 2025 export restrictions. The company projects 53% production growth in 2026 to approximately 16,100 tonnes total rare earth oxide output.

Lynas completed a A$750 million equity raise in August 2025 to fund expansion. The Kalgoorlie, Australia facility handles cracking and leaching, producing mixed rare earth carbonate for transport to the Gebeng, Malaysia refinery where separation occurs. Lynas began heavy rare earth production (dysprosium and terbium) in 2025 and expects to start samarium production in April 2026.

Power disruptions at Kalgoorlie - including significant outages in November 2025 - cost approximately one month of production in Q4 2025. Lynas is evaluating off-grid power solutions and working with Western Australian authorities to improve reliability. These operational challenges underscore why Chinese processing dominance persists: decades of infrastructure optimization that Western facilities are attempting to replicate under compressed timelines.

Lynas CEO announced retirement in January 2026 after navigating the company through the most volatile period in rare earth markets since 2010. Gina Rinehart, Australia’s wealthiest person, increased her stakes in both Lynas and Arafura Resources (~15.7% of Arafura) - a strong signal that strategic capital recognizes the value of non-Chinese supply chains even when operational execution remains challenging.

Lynas is reportedly in discussions with the US Department of Defense regarding rare earth price floor agreements similar to MP Materials’ arrangement. If implemented, this would provide the first non-US company with Pentagon-backed revenue guarantees - a significant escalation in allied rare earth security cooperation.

USA Rare Earth (private, planning NASDAQ listing) continues development of the Round Top deposit in Texas, which contains heavy rare earths. However, production remains years away and the path to commercial-scale processing has not been clearly demonstrated. Perpetua Resources (PPTA, Nasdaq) received $80 million+ in DoD grants for the Stibnite Gold Project in Idaho, which contains substantial antimony alongside gold. Permitting remains the critical path item.

China processes approximately 90% of global rare earths despite mining only 69%. That processing dominance cannot be replicated quickly. The chemistry is complex, the environmental regulations are stringent in the West, the economics don’t work without massive subsidies, and the skilled labor doesn’t exist.

When Ford’s German plant closures in 2024 were partly attributed to rare earth supply constraints, most analysts missed the connection. The April 2025 controls caused German rare earth imports to drop 50%. Electric vehicle production requires neodymium magnets for motors. No magnets? No production. It’s that simple.

And then there’s magnesium.

Magnesium represents the single greatest systemic risk in the entire critical minerals landscape. Not because it’s used in exotic military applications or cutting-edge technology. Because it’s essential for aluminum alloys that enable modern manufacturing. And China controls 85-95% of global production.

A single county - Fugu County in Shaanxi Province - produces 52% of global magnesium output. One county. Over half the world’s supply. The concentration is so extreme that regional power restrictions in Fugu can trigger global price spikes.

We saw the preview in 2021. Chinese power shortages curtailed magnesium production. Prices exploded from 16,500 yuan per ton to 70,000 yuan per ton. A 400% increase within months. European manufacturers faced shortages. The auto industry warned of production halts. Then Chinese power returned, production resumed, prices normalized, and everyone forgot the lesson.

The lesson was this: magnesium cannot be stockpiled. It oxidizes within three months. You cannot build strategic reserves the way you can with other metals. There is no buffer. There is no emergency backup supply sitting in warehouses waiting for a crisis. Magnesium supply must be continuous or it doesn’t exist at all.

This is what makes magnesium restrictions existential. Every other critical mineral discussed here - antimony, rare earths, gallium, bismuth, cobalt, tungsten, graphite - can be stockpiled. You can build months or years of inventory if you see restrictions coming. Supply disruptions are painful but manageable if you have warning.

Magnesium is different. A restriction would halt aluminum alloy production globally within weeks. Not months. Weeks. And aluminum alloys are everywhere. Aircraft fuselages. Automotive body panels. Beverage cans. Construction materials. Military vehicles. Spacecraft. High-speed trains. Consumer electronics casings.

5xxx and 6xxx series aluminum alloys specifically require magnesium. These alloys provide the strength-to-weight ratios that enable modern engineering. 5xxx series (aluminum-magnesium) alloys are used in marine applications, pressure vessels, and structural components. 6xxx series (aluminum-magnesium-silicon) alloys dominate automotive and aircraft applications. There are no substitutes that maintain equivalent performance characteristics.

The United States has no primary magnesium production. Zero. US Magnesium LLC operated a facility at the Great Salt Lake but has faced repeated shutdowns. Even when operating, domestic production served only a fraction of consumption. Import dependence is nearly absolute.

Companies attempting to revive Western magnesium production include Western Magnesium (MLYF, OTC), which has been working on continuous silicothermic reduction technology for years without reaching commercial scale. Australia’s Latrobe Magnesium (LMG, ASX) is developing extraction from brown coal fly ash. Both remain pre-production.

The timeline to rebuild meaningful Western magnesium capacity is estimated at five to seven years minimum, assuming billions in subsidies and acceptance of environmental impacts that Western countries have historically rejected. China’s cost advantages stem partly from Pidgeon process efficiency but largely from environmental externalities that OECD countries cannot politically accept.

Here’s the nightmare scenario: China announces magnesium export restrictions. Within two weeks, European and American aluminum smelters begin running out of supply. Within four weeks, alloy production halts. Within six weeks, aircraft manufacturing stops. Automotive production lines shut down. Defense contractors cannot produce vehicle hulls or aircraft components. The entire industrial base that depends on aluminum alloys - which is essentially all modern manufacturing - faces cascading failures.

No amount of emergency procurement can fix this. No strategic reserve can buffer the disruption. No alternative suppliers can ramp up in time. The restriction itself would be economically catastrophic, but the public wouldn’t understand why aluminum plants are closing. The explanation requires knowledge of metallurgy and alloy chemistry that 99% of the population lacks.

Maximum damage. Minimum comprehension. Perfect weapon.

And China hasn’t even restricted magnesium exports yet. That card remains unplayed.

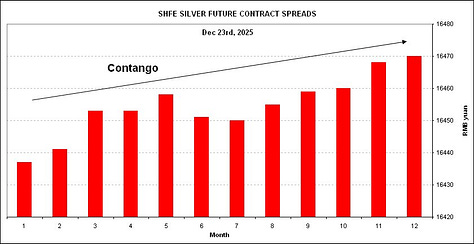

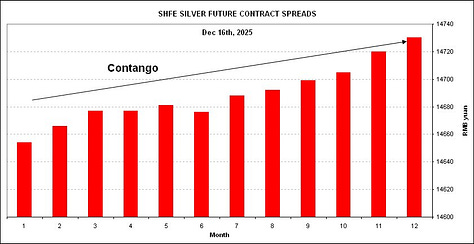

While Washington focused on semiconductor export controls and TikTok hearings, something else broke in global (precious) metals markets. Silent-silent-violent like someone I know constantly says… We’re at that violent part now.

On January 1, 2026, China’s silver export licensing came into effect. Only 44 companies received approval for 2026-2027. That’s it. The entire approved exporter list.

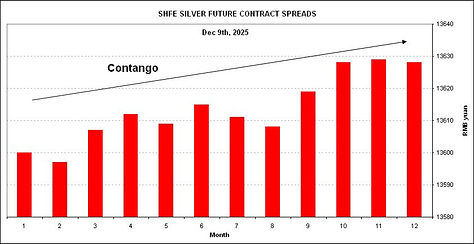

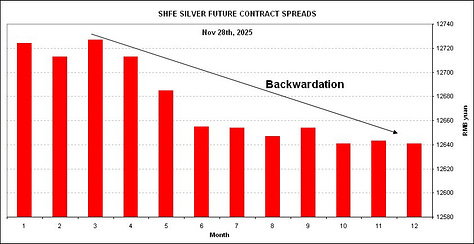

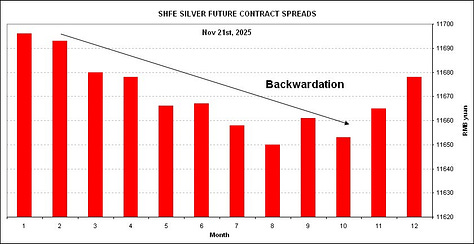

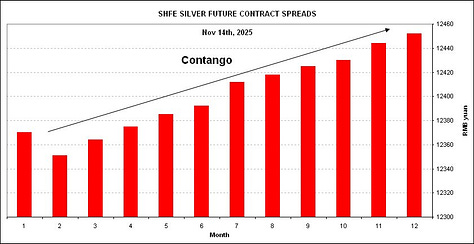

Shanghai silver premium over COMEX has been trending upwards since October and now exceeds $12 per ounce. Physical silver on Shanghai Gold Exchange trades at $108 while COMEX futures sit at $96. That’s a 12% premium. Historical Shanghai silver premiums averaged ~$2 per ounce. When premiums exceed $5, it signals severe physical tightness. Twelve dollars is unprecedented.

Then reports started surfacing from Japan and UAE. Physical bullion dealers selling - when they could find inventory - at $130 per ounce. COMEX spot showing $80. A 60% premium. The biggest decoupling in precious metals history. Gold occasionally sees 5-10% premiums during supply crunches. Silver sometimes trades at modest premiums in specific markets. But a 60% systematic decoupling between paper and physical prices across an entire region has never happened before in modern markets.

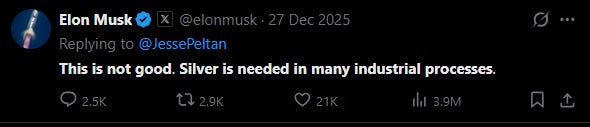

Elon Musk commented publicly on December 27, responding to a post about China’s upcoming silver restrictions: “This is not good. Silver is needed in many industrial processes”.

The mechanism is deliberate. China consumes over 50% of global industrial silver - solar panels, electronics, EV components. Industrial demand reached 58% of Chinese downstream consumption in 2024. The October 30, 2025 announcement of the January 1 implementation gave exactly two months warning. China locked in supply for their industrial buyers.

Western buyers? They scrambled for alternatives that increasingly do not exist.

The result? COMEX and LBMA show catastrophic delivery stress. COMEX registered silver inventories plunged to 23.1 million ounces in June 2024 - down 85% from approximately 150 million ounces in 2020. In the first two weeks of January 2026, 33.45 million ounces of silver were physically withdrawn for delivery. That’s a third of COMEX’s registered inventory in seven days.

LBMA silver vaults in London declined approximately 50% from their April 2020 peak of 35,667 tonnes. London silver lease rates - the cost to borrow silver for short-term needs - spiked to 30-40%+ in October 2025 and haven’t meaningfully declined. These rates mean that entities are so desperate for physical silver and cannot find it at any reasonable cost. Market participants describe the situation using technical terminology like “nobody’s got silver”.

The Russia-China precious metals realignment accelerates this bifurcation. Russia controls 40% of global palladium production. After London suspended Russian refiners from the LBMA Good Delivery list in April 2022, Norilsk Nickel redirected output to China. Previously 60% went to Western markets. Now the majority flows East.

First half 2025 data shows Russian precious metals exports to China surged 80% to $1 billion. Chinese entities reportedly purchase Russian metal below international benchmark prices, creating a two-tier pricing system. Western buyers pay premium prices for constrained non-Russian supply. Chinese buyers access Russian material at discounts.

Financial warfare doesn’t require sanctions or frozen assets. It just requires control over physical commodity flows and the patience to exploit pricing disconnects that markets cannot arbitrage away.

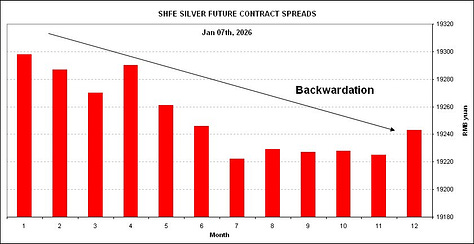

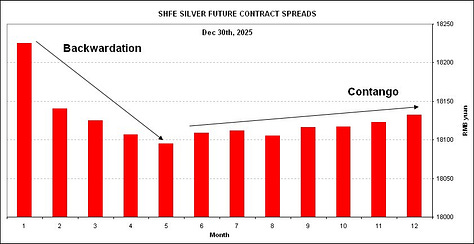

Even Shanghai went into backwardation in December. Backwardation means spot prices exceed futures prices - buyers willing to pay more for immediate delivery than future delivery. In commodity markets, backwardation signals supply stress. People need metal now and cannot wait. Western exchanges haven’t exhibited the same severity of backwardation already for a longer while, but the increased physical scarcity in Asia shows that the price increasingly does no longer reflect the value of the metal.

December 26, 2025. China announces sanctions on twenty US companies and ten individuals in retaliation for the $11.1 billion Taiwan arms package approved on December 17, 2025. The sanctioned list reads like a who’s who of American defense: Northrop Grumman, Boeing St. Louis, L3Harris Maritime, plus drone manufacturers Red Cat Holdings, Teal Drones, Epirus, Dedrone. Palmer Luckey, founder of Anduril Industries, makes the individual sanctions list.

The sanctions themselves are largely symbolic. US defense contractors have minimal direct China business due to existing export controls. You cannot sell F-35 components to Chinese customers anyway. The financial impact is negligible.

But the signal is unmistakable: if you sell weapons to Taiwan, you are permanently cut off from Chinese supply chains and the Chinese market. Not just for the transaction in question. Forever.

Extrapolate this forward. The United States wants to continue arming Taiwan. Congressional commitments are clear. But doing so requires supply chains wholly independent from China. Not just final assembly. Every component. Every raw material. Every processing step. Fully decoupled from mining through manufacturing.

Current US dependency makes this requirement absurd. The United States is 100% import-reliant for twelve critical minerals and greater than 50% reliant for thirty-one additional commodities. For rare earths specifically, 70% of imports came from China during 2020-2023. You cannot reshore what you never built in the first place.

The FY2024 National Defense Authorization Act requires DoD to achieve critical mineral supply chain independence from China by 2035. Ten years. DFARS 252.225-7052 prohibits, from January 1, 2027, procurement of systems containing neodymium-iron-boron or samarium-cobalt magnets produced in covered countries from mining through manufacturing. Two years.

DoD estimates $18.5 billion needed to address all critical material shortfalls. Current committed funding? Approximately $2.5 billion. The gap is roughly $16 billion and growing. Meanwhile, the number of materials in shortfall increased 167% from 2019 to 2023 - from thirty-seven materials to ninety-nine materials. The problem is accelerating faster than solutions.

Alternative timelines are sobering. GAO estimates fifteen years to rebuild rare earth supply chains. Industry estimates five to seven years for magnesium, gallium, and graphite processing. Bismuth and antimony? Three to five years if everything goes perfectly. Add the requirement to simultaneously rebuild industrial facilities, retrain skilled workers, establish quality control, achieve military specifications, and scale to volume production.

Now factor in costs. Reshoring increases production costs by 30-50% minimum. Sometimes 100%+ for materials where Chinese environmental externalities and state subsidies created artificial cost advantages. Higher costs mean fewer units procured. Fewer units mean slower iteration and technological lag. Every constraint compounds.

Meanwhile, China faces none of these constraints and can iterate faster with abundant, cheap components. Chinese defense contractors access domestic supply at lower prices. Chinese manufacturers benefit from vertical integration and state support. The decoupling meant to preserve American weapons industry may actually accelerate its relative decline.

The irony is brutal: the cost of selling weapons to Taiwan might be the very ability to defend it. Because if American munitions cost three times Chinese equivalents and take twice as long to produce, the war is already over before it even began.

While the United States liquidated its strategic reserves, China accumulated them on an unprecedented scale.

The contrast is stark.

The US National Defense Stockpile collapsed 98% in value from $9.6 billion in 1989 to $888 million in 2021. Current holdings meet only 37.9% of projected military needs and less than 10% of essential civilian needs in a national emergency. For antimony specifically, stockpiles declined from 27,000 metric tons in the 1990s to approximately 1,100 tons today - representing maybe 4-5% of annual consumption.

The number of materials classified as in shortfall increased from thirty-seven in 2019 to ninety-nine in 2023. A 167% increase in four years. The problem is accelerating, not improving.

Meanwhile, China’s National Food and Strategic Reserves Administration purchased a record 15,000 tonnes of cobalt in 2024. Estimated holdings include approximately 2 million tonnes of copper, 800,000 tonnes of aluminum, and 350,000 tonnes of zinc. The People’s Bank of China is estimated to hold 72.96 million fine troy ounces of gold - accumulated through consistent purchases that Western central banks dismissed as economically irrational. China imported a record 1.18 billion tonnes of iron ore in 2023.

The strategic implication is that when export restrictions hit, China can maintain domestic industrial production using reserves while Western manufacturers scramble for spot market supplies that don’t exist.

Turns out global markets stop being global when the supplier decides to nationalize flows. And just-in-time supply chains fail catastrophically when the critical inputs don’t arrive at all.

The antimony case proved the template works. Each following restriction will prove the template is repeatable. The question is not whether Beijing will weaponize mineral dominance again. The question is which material delivers maximum strategic impact with minimum public comprehension.

Magnesium restriction would cause immediate, cascading industrial failure. No stockpile exists. None can exist. No substitutes work. And production concentration is situated in a single Chinese county which provides maximum leverage. Public perception? Just above absolute zero.

Heavy rare earth processing cutoff would cripple precision weapons production. Public awareness exists but the fifteen-year timeline to alternatives is incomprehensible to most voters.

Bismuth represents the “nobody saw it coming” option. Essential for AI data center construction and pharmaceuticals. No stockpile exists. The tech industry is more vulnerable than defense to this particular chokepoint.

The November 2025 temporary suspension provided some breathing room until November 2026. It covered commercial end-uses which creates the illusion of de-escalation while military restrictions remained permanent and new restrictions on Japan and silver proceeded on schedule.

The pattern is clear: restrict, suspend, escalate elsewhere. Military end-use restrictions remain permanent. China’s processing dominance cannot be replicated within a decade. US strategic stockpiles remain at historic lows. Physical delivery stress on Western exchanges intensifies.

Million government investment contracts and emergency stockpiling efforts represent belated recognition of vulnerabilities. Too little, too late. Perhaps 15-20% of a $14+ billion estimate should be invested NOW. When China can escalate within days, and ramping up production is measured in years or decades.

China already knows the next metal.

They’re just waiting for the right moment.

Who knew you had to think beyond quarterly performance?

China’s long game is brilliant and frightening. We lost so much of our manufacturing to them. That part I understand well.

But this is staggering, and the very thing that can bring every country to bend a knee to China.

We were all blinded by low prices. China holds all the cards and we haven’t begun to feel the financial pain they can inflict on our economies.

Supply- chain hostage

Yikes 😬