SOFR, IOR and repo?

Indicators that (nearly) nobody are watching

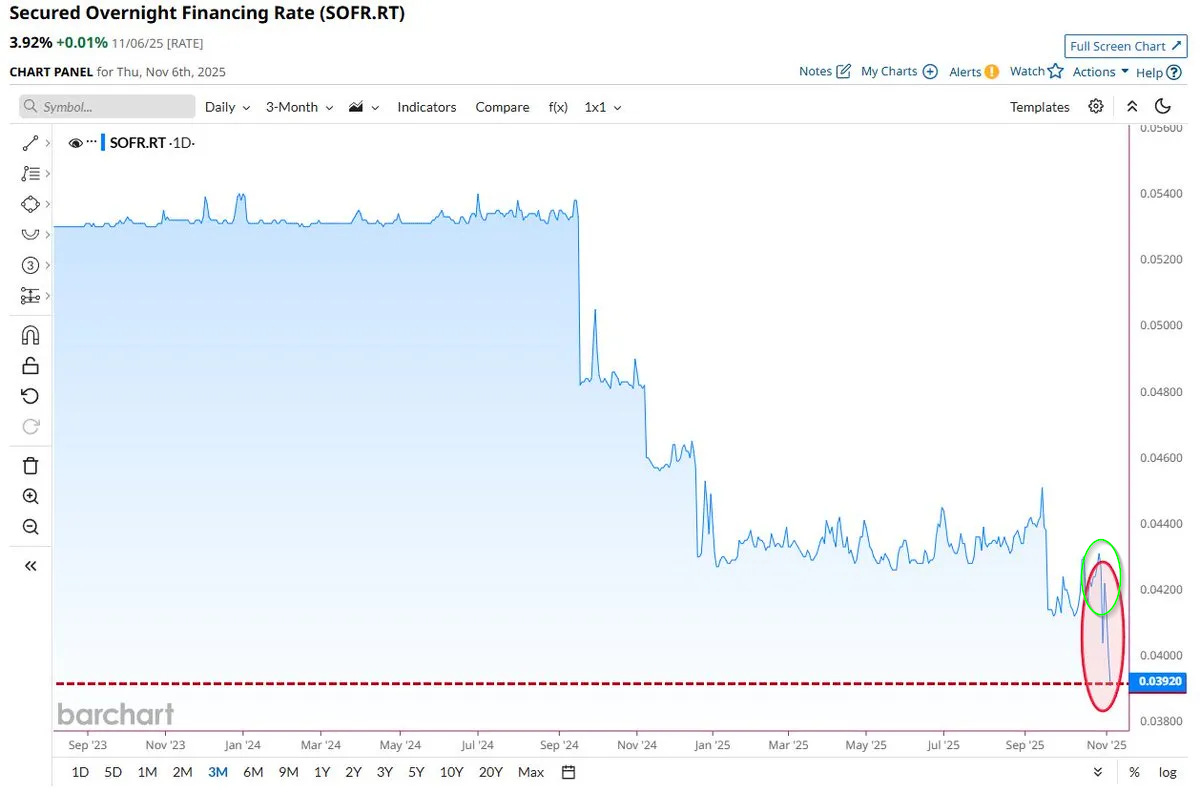

The financial system’s heart rate spiked hard on October 31, 2025, forcing the Federal Reserve to inject $50.4 billion into markets—the largest emergency intervention since the pandemic. An obscure interest rate called SOFR jumped to 4.22%, and the gap between that rate and the Fed’s safety valve stretched to its widest point ever. By November 6, SOFR had settled back down to 3.92%, but the October spike revealed something crucial: the financial system is running dangerously low on cash reserves, and when stressed, the plumbing can still clog fast.

If you did not understand any of that, don’t worry. I didn’t either at first when I started to look for obscure indicators that predicted the (future) health of our system.

So, if you know what SOFR and repo is, this is likely not an article for you and I can save you all of 5 minutes of your life: don’t continue reading.

But if you don’t, or if you want a refresher. Please let me explain how these money flows work and try to put it in perspective through everyday examples.

Let’s dive right in.

What is the repo market?

Roughly compared it is the financial system’s overnight pawn shop, except instead of guitars and jewelry, the collateral is U.S. Treasury bonds. Imagine you own a house worth $500,000 but you need $1,000 cash until tomorrow to cover payroll. You can’t sell the house for one day, but you could theoretically leave the deed with someone overnight, get your $1,000, and buy the deed back tomorrow for $1,000.03. That three-cent premium is the interest you paid for that overnight loan. Now scale that up to $1.5 trillion happening every single day between banks, hedge funds, money market funds, and other financial institutions. That’s the repo market—short for “repurchase agreement” because you’re selling something with a promise to repurchase it almost immediately.

But why does this market even exist?

Banks and financial firms have massive mismatches between their assets and their immediate cash needs. A bank might hold $10 billion in Treasury securities (safe, valuable, but not spendable) while simultaneously needing $2 billion in actual cash to settle trades, meet withdrawal requests, satisfy regulatory requirements, or handle payment flows. They can’t just sell those Treasuries because they need them for their balance sheet, for collateral elsewhere, or because selling would trigger unwanted tax consequences. So instead they temporarily “repo” them out—hand over the Treasuries as collateral, get cash for a night or a week, then reverse the transaction. The institution lending the cash gets ultra-safe collateral, and the institution borrowing gets liquidity without permanently selling assets.

SOFR

The Secured Overnight Financing Rate is simply the average interest rate charged across all these overnight Treasury repo transactions. Every morning at 8 AM Eastern, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York crunches the numbers from the previous day’s trades and publishes a single rate. If the average cost to borrow cash overnight using Treasuries as collateral was 3.92%, that’s your SOFR for that day. The “secured” part means the loan is backed by collateral (Treasuries), making it essentially risk-free. The “overnight” part means these are one-day loans. The “financing rate” part is just fancy talk for interest rate.

LIBOR

This SOFR rate replaced something called LIBOR, which was a complete disaster. LIBOR stood for London Interbank Offered Rate, and it was supposed to represent what banks charged each other to borrow. But LIBOR had a fatal flaw: it was based on what banks said they could borrow at, not actual transactions. Banks literally submitted their own estimates each day, and surprise surprise, they lied. Traders at major banks manipulated LIBOR for years to benefit their trading positions, leading to massive scandals and billions in fines. SOFR can’t be manipulated because it is not based on estimates—it is calculated from real transactions that actually happened. You can’t fake $1.5 trillion in daily trades.

Stress indicator/IOR

Under normal conditions, SOFR should trade slightly below the Federal Reserve’s target interest rate. The Fed currently targets a range of 3.75% to 4.00% for the federal funds rate (the rate banks charge each other for unsecured overnight loans). But understanding why SOFR trades where it does requires knowing about another rate: the Interest on Reserve Balances (IOR).

IOR is the rate the Federal Reserve pays banks on cash reserves they park at the Fed overnight. Currently 4.00%, it’s the ultimate risk-free rate for banks. Here’s another critical detail: only banks can access IOR. Money market funds, hedge funds, pension funds, and other non-bank institutions hold trillions in cash but can’t hold reserve accounts at the Fed. For them, the repo market is their best option to earn a return on overnight cash. This is why SOFR typically trades 5 to 10 basis points below IOR—the massive pool of non-bank lenders competing to deploy cash drives rates down below what banks can earn risk-free at the Fed.

Think of the repo market as having two main groups: banks (who usually need cash and borrow it) and non-banks (who have cash to deploy and lend it). Banks borrowing in repo pay SOFR rates. Non-banks lending in repo accept SOFR rates because they have no alternative—they can’t access IOR. When there’s abundant cash from money market funds seeking returns, they compete with each other and push SOFR down, sometimes well below IOR. From a bank’s perspective, if they have excess reserves, they’ll just park them at the Fed earning IOR rather than lending in repo at lower rates. But the non-banks keep the repo market functioning by accepting those lower rates.

When SOFR trades at 3.92% while the Fed targets up to 4.00% and IOR sits at 4.00%, everything is normal. The system has enough cash that non-bank lenders are competing for borrowers, keeping rates low. But when SOFR starts climbing above IOR and the Fed’s target range, something is seriously wrong. It means even the non-bank lenders who can’t access the Fed’s risk-free rate are getting better returns in the stressed repo market than banks can earn at the Fed. When SOFR spiked to 4.22% on October 31 while IOR was 4.00%, you’re watching pure desperation—borrowers so desperate for cash they’ll pay 22 basis points above the risk-free rate. That shouldn’t happen. The spread between SOFR and IOR is the real stress gauge. A negative spread means normal market function with ample liquidity. A positive spread, especially a wide one, means malfunction.

Reserves

These spikes all come down to reserves. Banks are required to keep a certain amount of cash in reserve accounts at the Federal Reserve—both for regulatory purposes and as a safety cushion. Think of reserves like the cash you keep in checking versus savings. Your savings might be bigger, but you need enough in checking to cover daily expenses without constantly transferring money. When the banking system as a whole has ample reserves—say $3.5 trillion sitting in Fed accounts—individual banks feel comfortable lending in the repo market because they know they have plenty left over. But when reserves drop to $2.8 trillion and keep falling, banks start getting nervous. They hoard cash instead of lending it, even overnight, because they’re not sure they’ll have enough to meet their own needs.

The Federal Reserve controls how many reserves exist through its balance sheet operations. When the Fed buys Treasuries and mortgage securities (quantitative easing), it creates new reserves—essentially printing money and depositing it into bank accounts. When the Fed sells securities or lets them mature without replacement (quantitative tightening), reserves disappear from the system. For the past few years, the Fed has been doing quantitative tightening, slowly draining reserves. This isn’t necessarily bad—the system had way too many reserves during COVID—but there’s a threshold below which you don’t have enough cushion. Nobody knows exactly where that threshold is until you hit it and SOFR spikes.

EOM/EOY

Month-end and year-end create predictable pressure points. Banks face regulatory scrutiny about their balance sheets at these dates, and they want to show they have sufficient reserves and aren’t over-leveraged. So on the last day of each month and especially at year-end, banks pull back from lending in the repo market. They’d rather sit on an extra $50 billion in reserves overnight to make their balance sheet look solid for regulatory snapshots, even if it means earning zero interest instead of the SOFR rate. This reduction in lending supply pushes SOFR higher. It’s like everyone trying to hoard groceries before a storm—even if there’s technically enough food, the panic creates shortages.

Standing Repo Facility

The Fed installed a safety valve called the Standing Repo Facility after the 2019 repo crisis. This facility allows banks and eligible institutions to borrow cash from the Fed overnight at a fixed rate (currently 4.00%) using Treasuries as collateral. It creates a ceiling on how high SOFR should go. If SOFR rises above 4.00%, banks can arbitrage the difference—borrow from the Fed at 4.00%, lend to the repo market at 4.22%, pocket 22 basis points of profit. That arbitrage brings more cash into the market and pushes SOFR back down. When the Fed’s Standing Repo Facility saw $50.4 billion in usage on October 31, it meant the arbitrage was so attractive that banks pulled that much cash from the Fed to supply the stressed repo market.

Application in our daily lives

Why does any of this matter if you’re not working on Wall Street? Because SOFR is now the benchmark rate for trillions in loans and financial contracts. When LIBOR was phased out in 2023, everything shifted to SOFR. If you have an adjustable-rate mortgage, there’s a good chance it is tied to a SOFR average (usually the 30-day or 90-day moving average). Business loans, student loans, corporate bonds, and derivatives all reference SOFR. When SOFR moves, your borrowing costs move. More importantly, persistent SOFR volatility signals that credit conditions are tightening. If banks are struggling to get cash overnight, they become less willing to make new loans and more likely to raise rates on existing variable-rate products.

Early warning signal

SOFR also acts as an early warning system for financial stress. The repo market is the circulatory system of modern finance—cash flows through it to keep everything else functioning. When SOFR suddenly spikes, it means something is wrong with circulation. Maybe reserves are too low, maybe a major institution is in trouble and others are pulling back, maybe regulatory pressures are creating artificial scarcity. Whatever the cause, it shows up in SOFR before it shows up in stock prices or credit spreads. By the time the broader market notices financial stress, the repo market has usually been flashing warning signs for days or weeks.

Liquidity flood

But here’s the interesting bit: after that EOM October spike to 4.22%, SOFR didn’t just settle back to normal—it fell off a cliff. In one week, SOFR had collapsed from the 4.20% range down to 3.92%, a dramatic drop that signals something equally important but opposite to the stress spike. When the cost of overnight money collapses, you’re not watching stress—you’re watching a liquidity flood.

Think about what cheap overnight funding means. If you’re a hedge fund and you can suddenly borrow cash at 3.92% instead of 4.22%, that 30 basis point difference is pure profit on leveraged positions. Cheaper funding encourages more leverage, which fuels higher risk appetite, which drives asset prices up. When SOFR drops sharply, it is not because the system is healthy and stable—it is because so much cash is sloshing around that lenders are competing for borrowers, driving rates down. This is the opposite problem: too much liquidity instead of too little.

Several factors converged to create this liquidity surge. The Treasury General Account (TGA)—that government cash hoard that swelled to over $1 trillion during the shutdown—will start draining once the government reopens. Every dollar that flows out of the TGA and into the economy adds liquidity to the banking system. The Fed announced that quantitative tightening will end in December, meaning they’ll stop draining reserves. Some Fed officials have even hinted at expanding the balance sheet again to stabilize reserves at a higher level. Layer all of this together and you get a massive shift in liquidity conditions—the market isn’t reacting to narratives, it is front-running a regime change.

Two-way indicator

This is why SOFR works as a two-way stress indicator. A spike above the Fed’s target signals desperation for cash and system stress. A collapse below the Fed’s floor signals excess liquidity and potential for overleveraged risk-taking. Both extremes matter, just for different reasons. The spike in late October showed the system running too lean on reserves. The collapse in early November showed liquidity about to flood back in, encouraging leverage and risk appetite. Neither is necessarily “good” or “bad”—they’re signals about what’s coming next in credit conditions, asset prices, and financial stability.

Take-away

Hopefully the things I’ve described reveal why it makes sense to watch SOFR rates. It’s transparent, real-time, and factual. It is not some theoretical model or analyst estimate—it is the literal price of overnight cash in the safest corner of the financial markets.

⤴ When that price suddenly jumps, when the spread to the Fed’s target widens, when the Standing Repo Facility sees heavy usage, you’re watching the system strain in real time.

⤵ When that price collapses and funding gets cheap, you’re watching liquidity flood in and leverage build up.

This machinery captures both stress and exuberance, both scarcity and abundance.

A very helping article, although I must say, a little demanding for an amateur like me. You connect concept after concept so fast that I often get lost. It would require me hours to patiently break down your points and integrate the content, certainly more than a 5 minute read, infact more than 20. But I thank you for your great job.

Well. I notice that You manage with ease SOFR and IOR stuff (I know for sure cause You're able to explain it with easy words) . So U could shed some light on current financial system plumbing. I'm so disperate for losing Zoltan contribute that sometime I try to infer what's happening from the titles of the articles paywalled on his website. I'm learning a ton from his sources (pippa malmgren blog, perry mehrling work and dale c copeland books)