Musing about AI & robotics

The automation paradox

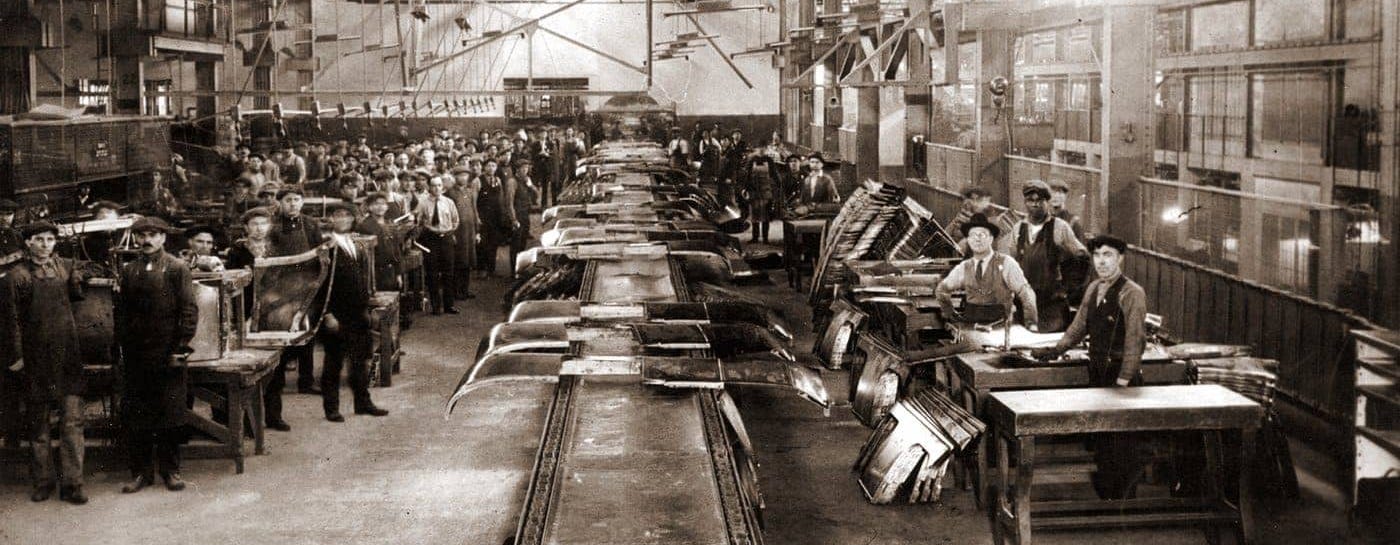

When humans first mastered fire, elders worried there’d be nothing left to do. The wheel arrived, and people feared unemployment would follow. Electricity lit up cities while workers trembled about their jobs disappearing. Henry Ford’s assembly lines made cars affordable, and everyone predicted mass joblessness. The industrial revolution mechanized production, and society braced for economic collapse because soon there’d be nothing left to do. Computers arrived and office workers were certain automation would eliminate their positions. The internet connected the world and economists warned of widespread job destruction as e-commerce replaced brick-and-mortar retail.

There’d be nothing left to do.

Except there always was.

Every technological leap brought the same warnings, the same hand-wringing about redundant workers, and the same conviction that this time would be different.

And every time, new jobs emerged.

The displaced factory worker became the telephone operator. The telephone operator became the computer programmer. The retail clerk became the fulfillment center worker. The pattern held for centuries: technology eliminated specific tasks but created entirely new categories of work.

Until now. I truly hope I’m wrong.

What’s happening right here right now isn’t another industrial shift. It’s a fundamental break from everything that came before. And the fracture is starting at the bottom of the ladder.

Walking through Xiaomi’s “dark factory” in Changping and you will thouroughly understand the scale of what’s happening.

The facility produces one smartphone every second.

No workers.

No lighting.

No lunch breaks.

Just 81,000 square meters of robots assembling devices in near-total darkness, monitored by infrared sensors and LIDAR. The company invested $330 million to eliminate humans from the production line entirely.

Annual capacity: 10 million devices.

Human staff required: effectively zero.

It’s not an isolated experiment. Foxconn replaced 60,000 workers with robots in a single Kunshan plant back in 2016. China’s robot density hit 392 per 10,000 manufacturing workers in 2023, nearly triple the global average. Western executives return from factory tours in Shenzhen describing production floors that once employed thousands now running with a handful of technicians monitoring screens.

The difference between this and Ford’s assembly line? Ford needed workers to operate his machines. These machines operate themselves.

But here’s what makes now different from every previous automation wave: past automation made manual work more efficient. AI is cutting off access to the starting point for knowledge careers.

Entry-level positions are vanishing at an unprecedented rate. In the first seven months of 2025, AI-driven automation directly caused over 10,000 job cuts in the U.S., according to outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas. College-educated Americans aged 22-27 face 5.8% unemployment—the highest in four years. Entry-level job postings in professional services dropped 20% year-over-year, hitting the lowest level since 2013.

Microsoft’s CEO revealed that 30% of company code is now AI-written. When those layoffs came, 40% targeted software engineers. Not the senior architects. Not the principal engineers. The junior developers writing the routine code that AI can now generate instantly.

Shopify’s CEO told staff directly: no more new hires if AI can do the job. Duolingo’s CEO uses “AI fluency” to determine who gets hired and promoted. McKinsey deployed thousands of AI agents throughout the company, picking up tasks previously handled by junior consultants. The pattern repeats across every sector. Customer service representatives—80% automation risk by 2025. Data entry clerks—95% automation potential. Retail cashiers—65% facing replacement. Marketing assistants—31% reduction since 2022.

The jobs getting automated first share a common trait: they’re the ones where people learn by doing. Where you make mistakes on low-stakes work and figure out the patterns. Where you build the foundational knowledge that eventually qualifies you for senior positions.

And that’s where this story stops being about job statistics and starts being about something far more dangerous.

When you eliminate entry-level positions, you’re not just cutting costs. You’re severing the knowledge pipeline that creates expertise. A junior software engineer doesn’t just write code—they learn how systems fail, how bugs emerge, how architectural decisions compound over time. A junior analyst doesn’t just process data—they develop intuition about what numbers actually mean, which patterns matter, which correlations are spurious.

You can’t shortcut that process. You can’t promote someone from zero experience to senior architect just because you need someone to verify AI outputs. The expertise doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It builds through years of hands-on work, mentorship, failure, and learning from mistakes.

When you train an AI model, you do it once. Copy it instantly. Deploy it everywhere. But training a human expert? That takes decades of experience, dozens of projects, countless iterations of getting it wrong and figuring out why. You can’t compress a ten-year learning curve into a weekend bootcamp.

Which means we’re creating this bizarre situation where we’re eliminating the exact positions that teach people how to do the senior roles we so desperately will need. The senior engineers who can catch AI hallucinations in generated code. The senior analysts who can spot when AI recommendations are technically correct but strategically disastrous. The senior managers who understand their business deeply enough to know when AI-generated insights are missing crucial context.

Where do those senior people come from in five years? Ten years? You can’t hire someone with ten years of experience if nobody’s been doing the work for ten years. The pipeline doesn’t just slow down—it breaks entirely.

And companies are only now starting to realize what they’ve done. You automate away your entire junior staff, then discover your senior people are aging out, retiring, leaving, burning out. You need to replace them, so you look for candidates with deep expertise. Except you’ve spent the last five years not hiring anyone at that entry level. The candidates don’t exist anymore.

The automation advocates will tell you AI can train itself, that systems will learn and improve without human oversight. But who checks the AI’s work? Who verifies the outputs? Who catches the subtle errors that compound over time? You need humans with genuine expertise to do that. And those humans need to have learned their expertise somewhere.

This isn’t just a problem for individual companies. It’s an entire generation of professionals who will never develop the depth of knowledge needed to work at the highest levels. Because the training grounds—those entry-level positions where you learn by doing—no longer exist.

The irony!

We’re building AI systems that require expert human oversight to function safely and effectively. And we’re simultaneously destroying the career pathway that creates those human experts.

It’s like burning down all the medical schools while demanding more doctors.

But that experience gap, as profound as it is, turns out to be just a symptom of a much larger structural problem. Because even if we somehow solved the expertise issue—even if we figured out how to train people without entry-level jobs, or if AI genuinely became good enough to verify its own outputs—we’d still run headfirst into an economic paradox that can potentially break our entire current system.

Modern capitalism operates on a deceptively simple circuit:

Companies employ workers → Workers earn wages → Wages fund consumption → Consumption generates revenue → Revenue funds employment.

It’s a closed loop that has powered every economy since like forever.

Breach any link and the whole thing collapses.

The current AI/robot automation severs the first link. Eliminate employment but keep consumption going. How’s that going to work?

But everybody is too busy optimizing quarterly profits to even notice.

“If AI does everything, then who is left to buy AI-generated goods and services?”

That question isn’t coming from scared workers. It’s coming from the AI executives themselves. The people building these systems understand the contradiction better than anyone. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei warned in May 2025 that AI could eliminate half of entry-level white-collar jobs within five years. Not “might eliminate”. Could eliminate. The man building the technology is telling you what’s coming.

Think about that dark factory in Changping. Xiaomi produces 10 million smartphones annually with effectively zero human labor. Incredible efficiency. Maximized profits. But scale that model across the economy and ask yourself: who buys those 10 million phones if the factory workers are unemployed? If the retail workers got automated away? If the customer service representatives are gone? If the marketing assistants lost their jobs?

First movers into automation reap enormous benefits. Lower costs, higher margins, competitive advantage. Your company cuts labor expenses by 40% while your competitors still employ humans. You win. Shareholders celebrate. Stock price soars.

But here’s what happens next. Your competitors see your success and automate too. Their competitors follow. The race to automate spreads across the industry, then across every industry. Everyone’s cutting costs and boosting efficiency simultaneously. And suddenly you’re all producing goods very efficiently for a market that’s shrinking because you collectively automated away your customer base.

And it’s not even a hypothetical future scenario.

We’re watching it happen in real time!

The World Economic Forum projects 40% of employers will reduce their workforce where AI can automate tasks. Not “might reduce” in some distant future. Will reduce. Present tense. Happening now.

For every 10 jobs AI eliminates, only ~7 new roles emerge. And ~5 of those new AI-related positions require a master degree. So you’re eliminating entry-level jobs by the millions and replacing them with a much smaller number of highly specialized roles that require advanced degrees most people don’t have.

The scale problem gets worse when you examine the timeline. McKinsey’s projected in 2023 certain automation levels (for 2030)… In ‘24 they already had to revise them upward by 25% because generative AI accelerated faster than anyone anticipated. The forecasts that seemed aggressive a few years ago are now conservative. It’s not going to be a gradual transition that spans decades. We’re in the middle of a rapid change of traditional employment structures.

Previous industrial revolutions played out over generations. When the automobile replaced the horse and buggy, you had fifty years to adapt. Blacksmiths became mechanics. Stable workers became factory workers. The economy created new categories of work faster than it eliminated old ones, and people had time to retrain, to learn new skills, to find their place in the new order.

But AI capabilities are doubling every few months.

It’s not only the neck-breaking speed of things, it’s also the globality of it.

Everything everywhere all at once.

China’s robot density: 470 per 10,000 workers. Germany: 429. The U.S.: 295 (lagging, but climbing fast). The International Federation of Robotics reports global industrial robot installations doubled over the past decade, reaching 542,000 new units in 2024. Nobody can afford to fall behind, which means everyone’s automating at once, which means the consumption crisis arrives everywhere simultaneously.

You can’t solve a global consumption crisis with local solutions. If the entire world is automating away their workforce at the same time, you can’t export your way out of the problem. There’s no foreign market with employed consumers to buy your efficiently-produced goods. Everyone’s in the same boat, and that boat is sinking.

Universal Basic Income gets proposed as the solution to this consumption paradox. Give everyone free money. Whether they work or not. Let them maintain their purchasing power, keep the consumption engine running. Elegant in theory. Catastrophic in practice.

Think through the logic. Companies build AI-powered factories to maximize profits and minimize costs. Those profits get taxed to fund UBI payments. The UBI money gets spent on products from the AI-powered factories. Which generates the profits that get taxed to fund more UBI payments.

It’s a circular flow that makes sense until you ask: where’s the growth? Where’s the innovation incentive? Why would anyone invest billions in developing the next best thing if the government just taxes away the returns and redistributes them? The Russians tried that. We all know how that ended.

The entire motive that drives technological advancement disappears. You’re asking companies to perfect automation so the government can confiscate the gains and hand them back to the people who got automated out of work. Why continue innovating under that system? Where’s the incentive?

The Soviet Union tried divorcing innovation from profit incentives. It didn’t end well. People need a reason to build better systems, a reason to take risks, a reason to invest years of their efforts into advancements.

Remove those reasons?

You’ll get stagnation.

If you do that, I can guarantee you that the technology will stop improving. The efficiency gains will plateau. And you’re left with a system that’s locked into a specific level of productivity with no mechanism to advance further.

But let’s say that you don’t implement UBI or some heavy (automation) taxes. Say that you let the market forces work. So companies will automate freely, reap all the profits, and the shareholders will benefit enormously.

This will lead to a wealth concentration among a tiny fraction of people who own the AI systems and robot factories.

Everyone else? Economically irrelevant.

Either way that I see, you get a consumption crisis. Just from a different angle. The automated factories can produce abundant goods very cheaply, but nobody can afford to buy them because nobody has any income. Demand collapses. Markets shrink. Even the owners of the automation will eventually suffer because they can’t extract profits from sales that don’t happen.

There’s no escape from this paradox within any of our current economic structures. Be it Western, Chinese, Russian. No1 is ready for what comes next.

Either you kill innovation through redistribution, or you kill consumption through unemployment. Pick your poison. Both paths lead to economic collapse, just through different mechanisms.

Some economists argue market forces will self-correct. Lower prices from automation will increase demand. New industries will emerge. Displaced workers will find new roles. It’s the same argument that’s been made during every industrial transition, and it’s always been correct before.

Except I feel this time is truly different. The fundamental nature of the automation changed.

When Ford automated car production, he needed workers to operate his assembly lines. And he understood something crucial about the consumption loop: he raised wages to $5 a day—more than double the average—specifically so his workers could afford to buy the cars they built. Ford grasped the paradox intuitively. You can’t sell cars to unemployed people. When computers automated office work, they needed humans to input data and interpret outputs. Every previous wave of automation augmented human labor or displaced specific tasks while creating new ones.

AI and robotics propose to eliminate human labor entirely across broad categories of work.

But can you create new categories of human work? When AI can do virtually any cognitive task? And robots can perform most physical labor?

What’s left?

What job category exists that’s immune to automation when we’ve got AI that can write code, create content, analyze data, make decisions, and robots that can assemble products, drive vehicles, operate machinery, and perform surgery?

The optimists will point to healthcare, education, creative work, personal services—domains where human connection matters. Except AI is making inroads there too. AI tutors personalize education better than human teachers can scale to. AI therapists provide mental health support 24/7 with infinite patience. AI can already create art and music that’s indistinguishable from human-generated content.

Even the “safe” jobs aren’t safe anymore. They’re just next in line.

I know it’s hard to acknowledge, but maybe there isn’t a new category of work waiting to emerge? Maybe we’ve reached a genuine endpoint where machines can perform every economically valuable task better, faster, and cheaper than humans? Maybe the pattern that held for thousands of years—technology eliminating some jobs but creating new ones—has finally broken?

If that’s true, then we’re not facing a transition period followed by a new equilibrium. We’re facing a permanent state where human labor has no market value. Where the entire concept of employment as the basis for economic participation becomes obsolete.

You could argue that’s utopian. A world where AI provides abundance and humans are free to pursue art, philosophy, exploration, relationships—anything meaningful beyond mere survival. Star Trek’s post-scarcity paradise where work is optional, replicators provide material goods on demand, and everyone’s basic needs are guaranteed while humanity focuses on self-improvement and discovery.

Except abundance without distribution is just concentrated wealth. And distribution without employment requires political mechanisms that don’t exist and economic incentives that contradict everything that’s driven progress for centuries. Getting from here to that theoretical utopia requires restructuring civilization from the ground up.

Good luck achieving that political consensus when you’ve got mass unemployment, economic instability, and populations that are angry, scared, and looking for someone to blame.

More likely, we get the dystopian version. Wealth concentrates amongst the few, a small elite which lives in extraordinary abundance while the formerly middle class joins the expanding ranks of the economically irrelevant. Geographic inequality widens. Political tensions escalate. Social institutions built on the assumption of full employment collapse under the weight of permanent joblessness.

Current evidence at least points in that direction. Entry-level jobs are vanishing. Wages are stagnating while productivity soars. The people benefiting from automation aren’t the workers being automated—they’re the shareholders of the companies doing the automating. Return on capital is rising. Return on labor is falling even more.

That gap is accelerating, not closing.

As in the past, when change happens gradually, compensation mechanisms can develop organically. New industries emerge, and displaced workers will find alternatives.

Society adapts.

But when those changes happen exponentially, those mechanisms shatter. New industries employ a fraction of displaced workers and require specialized skills taking years to develop. Safety nets designed for temporary unemployment collapse under structural joblessness. Political structures built on full employment have no framework for permanent labor redundancy.

“Learn to code”.

“Pivot into AI”.

“Become a prompt engineer”.

Except AI writes better code than junior developers, creates art that sells, generates content that engages. Even emotional intelligence has limits—an AI that perfectly simulates empathy. Is it any different from the real thing?

The underlying problem is also our biology. Our learning speed is fixed. Our adaptation capacity is limited. Our biological processing power can’t double every eighteen months the way computing power does.

You can’t win this race against exponential improvement when you’re linear. You just lose more slowly.

Which brings us back, finally, to the question that economics keeps trying to avoid: when nobody works, who buys?

The answer, increasingly, looks like: nobody.

And that’s not a bug in the automation revolution. It’s the feature that breaks capitalism itself. The economic system that created the incentive to automate is the same system that requires mass employment to function. You can’t have both maximum automation and broad-based consumption. The two goals are mutually exclusive.

Something has to break. Either the drive toward automation slows dramatically—unlikely when it offers such enormous competitive advantages—or the consumption base erodes until markets collapse under their own efficiency. Those are the options. Everything else is just variations on those two themes.

We’re watching this play out in real time. Every quarter, another major company announces AI-driven layoffs. Every month, another category of work becomes automatable. Every week, another startup launches promising to do some human task better and cheaper with machines. The drumbeat is constant, the direction is clear, and nobody’s steering.

Because steering would require a global coordinated action across governments, industries, and economic systems. It would require agreeing that maybe some forms of efficiency are socially destructive even if they’re economically optimal. It would require putting long-term systemic health ahead of short-term competitive advantage. It would require reimagining how economies work.

And nobody is doing that. Everyone’s just optimizing their own piece, hoping someone else solves the bigger problem, assuming it’ll all work out somehow because it always has before.

You can produce infinite goods with infinite efficiency in infinite darkness, automated perfectly by tireless machines that never sleep and never err. Marvel at the productivity. Celebrate the innovation. Optimize the margins. Automate the future.

Just don’t ask who’s left to buy any of it.

Because the answer is the same as asking what jobs will be left to do when the automation is complete.

There’s nothing left to do.

And nothing left to buy, either.

Fascinating. Still hoping you're wrong, just like your last article!

A friend's granddaughter, 17 y/o, is aiming for a career as a dentist. She figures that the profession will be safe from AI/robotic intrusion. I think she's overly optimistic. I'm happy to be 74 y/o.